Credits:

Nader Ardalan ,Graduate School of Design Harvard University

Introduction:

Learning to manipulate clay, stone, marble, and wood, man penetrated their properties, and his techniques gave expression to his aspirations toward the divine. In architecture, environmental harmony was known to the Chinese, the Indians, the Greeks, and others. It produced the temples of Karnak, the great mosques of Islam, and the cathedral of Chartres in France. Hassan Fathy

In the course of human cultural and scientific development, we can identify five transformational phases of history to the present.2 From the Paleolithic and Neolithic we evolved into the phase of the Classical-Traditional cultures of the great religions. In the last five hundred years we have gradually transformed into the Scientific-Technological phase and have now reached a threshold where the dominance by science and technology under the control of modern corporations and their reign of quantity and material consumerism is now threatening the very existence of life on earth.3 Yet, we are still hesitant to awaken to the fact that for a species to remain viable, it must establish a niche for itself that is holistically beneficial both for itself and for the well being of its surrounding context.4 This “beneficial niche” needs an attitudinal change, a transformation to what some have termed an emerging Ecological Age that will succeed the Technological age and foster a deep awareness of the sacred presence within each aspect of the universe and man’s integral part in this web of existence. 5Caught between the traditional past of religious beliefs and the yet not fully formed and comprehended new cosmology of the next Ecological phase of human consciousness, human being sexist in a transitional situation that is precarious and yet full of potential. Traditional Abrahamic religions have taught that the Divine is transcendent to the natural world; there fore they hold that we must negate the natural world as a locus for the meeting of the Divine and the human. This makes the conception of the natural world as merely an object to serve man’s material needs and this attitude has led to the plunder and near destruction of the natural resources of the earth by contemporary society.6 In Islam, this tendency is some what mitigated since man’s responsibility toward the natural environment evolves from his role as God’s Khalifa(inheritors or vicegerent) on earth. In this regard the Quran says, ‘He is that has made you inheritors in the earth: if, then ,any do reject, their rejection (works) against themselves’.

The Hadiths frame this responsibility within the two principles: unselfish utilization of natural resources and preservation of the natural balance as good stewards of nature.8 However, even these worthy cultural precedence are mostly not heeded in contemporary thought and action by decision makers in the Middle East

Perhaps, the social revolutions being experienced around the world and most recently over the last two quarter generations in the Middle East, highlighted by the recent “Arab Spring”, are testaments to the material pressures of a world that has multiplied to seven billion population and we are now 50% urbanized; water and food supplies have become increasingly more scarce; issues of income discrepancies, unemployment, financial crises and civil injustice characterize a growing number of contemporary societies. Faced with these daunting, disruptive forces, we seem to have no common ground visions or functional cosmology to guide us to viable solutions. Yet, at no time in history have humans had such access to the vast qualitative and quantitative knowledge made available to us that could discipline and generate sustainable new directions for a noble human survival

Within this panorama and the limits of this article, my interest is to focus on one pivotal question related to the future of our urban built environments. In particular, the question is: How can holistic approaches to ecological spirituality inform and influence the form and life patterns of current and future cities in the Middle East? What is the potential of the city to spiritually uplift the human spirit, contextualize and symbolize our shared “human condition,” accommodate inclusive communal activities and rituals that give meaning to our lives, and provide connections to knowledge and understanding of the transcendent dimension of existence in architecture and the urban setting?9 Perhaps, one way to do that is to look at positive examples in the past and elicit key design principles; observe the shortcomings of this subject in the present; incorporate the vast new knowledge available to us about ecological urbanism and then proceed to suggest what innovative design paradigms might help produce the sustainable city sublime of the future in our region of the world? What have been the holistic environmental, social, cultural, economical forces and urban design policies that have produced the sublime places, the beautifully vital cities of the world and the architecture that we cherish and are transformed by?

Once we have explored and understood the elements of such transformative places that produce in us a sense of “wondrous awe” and integrated them with new criteria of ecological spirituality, we may proceed in the next phases to study how these considerations, as basic principles, might help produce the city sublime of the future and rehabilitate our existing cities. Within the limits of this short essay, might it be possible to gleam some lessons of what has been the role of spirituality in the more memorable and beautiful built environments of the Middle East? What are the highlight ‘spiritual’ foundations that have given birth, sustained, made grow, and (when lacking) caused the death of cities in this region over the last ten millennia?

Selected case studies Gobekli TepeThe recent excavations of Gobekli Tepe, located in the mountains of the Kurdish districts of southern Turkeyat the headwaters of the Tigris River and dated at 9600BC, is regarded as an archaeological discovery of the greatest importance since it could profoundly change our understanding of a crucial stage in the development of human societies 10. It seems that the erection of monumental complexes was within the capacities of Neolithic hunter-gatherers and not only of the latter sedentary farming communities in Mesopotamia in the3rd C BC, as had been previously assumed. In other words, as excavator Klaus Schmidt of the German Archaeological Mission puts it: “First came the temple, then the city.” This revolutionary hypothesis will have to be supported or modified by future research. The site contains 20 round, (now) subterranean structures (four of which have been excavated). Each stone building has a diameter of 10-30 meters with massive T-shaped limestone pillars decorated with carved animal figures ,the tallest are 6 meters high and are the most striking feature of the site. (See fig. 1)

These temples articulated belief in gods only developing later after 5000 to 6000 years in Mesopotamia. As the article in National Geographic entitled: The Birth of Religion described about the recent archaeological finds at Gobekli Tepe, it may have been the need to share our awe for the divine or give thanks to the ineffable that may have propelled humankind to build its first sacred spaces and thus the nucleus of a settlement … Not the accumulation of goods and wealth during the Neolithic time (as today’s narrative goes) … The deep and pure desire to be with others in a profoundly inspiring place is at the root of what is spiritual … The brotherhood of humanity … Returning to the one, being at oneness, and also being many in collaboration and peace, springing out of an spiritual source

Thebes

Ancient Thebes was founded in 3200 BC on the east bank of the fertile Nile River, which served as an essential part of ancient Egyptian spiritual life. Hapy, the god of the annual floods, was believed to irrigate the surrounding fields, supporting the abundant agricultural crops that made Egypt the breadbasket of the Middle East. Both Hapy and the pharaoh were thought to control the flooding.

The Nile was considered a symbolic causeway from life to death and the afterlife. The east, associated with birth and growth, became the site for the Temple Complex of Karnak—with its sacred lake—and the Temple of Luxor, both constructed on the eastern bank of the Nile. In contrast, the west was regarded as the realm of death, reflecting the journey of the sun god Ra, who was reborn each morning and died each evening as he crossed the sky.

To the west of the Nile lay the Theban Necropolis, including the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens, set against the pyramidal Mt. Al-Qura (“the Peak”). Egyptians believed that to enter the afterlife, they had to be buried on the side of the Nile that symbolized death.

The annual Opet Festival celebrated fertility and renewal. It featured the cult statue of Amun-Re, the chief deity of Thebes, being transported down the Nile from Karnak to spend time with his consort Mut, the Earth goddess.

In summary, Thebes was a spiritually and ecologically integrated landscape—rich with meaning, ritual, and significance for both its inhabitants and the broader Egyptian civilization (see Fig. 2).

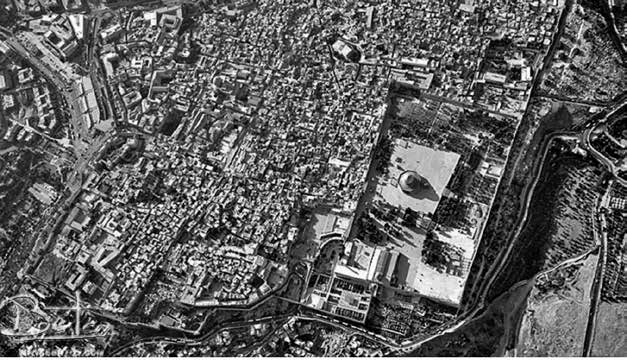

Jerusalem

The Old City is symbolically the archetypal “City on the Hill.” Situated at the ecological threshold between Mediterranean and desert bioclimatic regions, its hilltop location actually lies in a basin, bounded on two sides by ridges such as the Mount of Olives and Mount Scopus, which run north to south. Immediately to the east of the walled city is the Kidron Valley, while to the west and south lies the Hinnom Valley.

With a history spanning over 5,000 years, Jerusalem holds sacred status in the three great monotheistic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—making it a holy city for more than a third of the world’s population. The urban fabric is defined by compact limestone structures of one to three stories, their silhouettes marked by domes, vaults, minarets, and steeples. These are spatially organized around a network of public and private courtyards and squares, all accessed through winding pedestrian-only pathways.

The richly textured and small-scaled parts of the city are enclosed by massive stone walls, which are punctuated by seven historic gates leading into its four quarters. Near the center rises the iconic Dome of the Rock, its golden-hued cupola visible above the cityscape.

The unique aura of the Old City owes much to the balanced social patterns and behaviors of its diverse residents—of all faiths, ethnicities, and income levels—who have traditionally lived pious and community-centered lives. This traditional lifestyle, along with its associated rituals, values, and visual forms, continues to evolve in response to contemporary opportunities, maintaining the city’s vitality precisely because it is not static¹² (see Fig. 3).

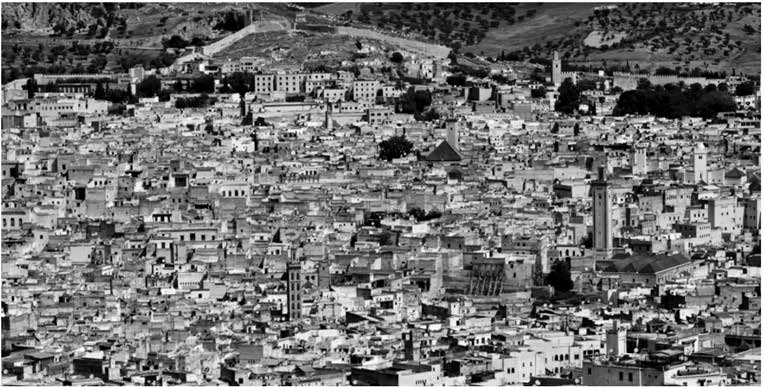

Fez

Fez was founded by Berbers on the banks of the Fez River in the Atlas Mountains in 789 CE. The city experiences a Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers and chilly, wet winters. Fez is arguably the largest and most enduring medieval Islamic settlement in the world. It remains Morocco’s spiritual and cultural heart—often referred to as the soul of the nation. As one local remarked, “It’s the last bastion of what Morocco really is.”

One need only witness the daily procession of candle-bearing mourners entering the tomb of Moulay Idriss II—believed to be a great-great-grandson of the Prophet Mohammed—to feel the city’s profound connection to its past.

The Kairouyine Mosque, one of the oldest and largest in Africa, was established in 859, along with the associated University of Al-Kairouyine, a center of learning since the early Islamic period. Fez’s Golden Age occurred during the 14th century, yet its influence continues to permeate the spiritual life of Morocco to this day.

Few places on Earth feel so saturated with symbolic meaning: in the intricate patterns of hand-knotted carpets; in the tattooed faces of Berber peasant women; in the cosmic swirls of carved plaster; in the haunting voices of Sufi and Gnawa singers; in the mastery of traditional craftsmanship; and in the aromatic complexity of its cuisine¹³ (see Fig. 4).

The city’s layout follows the principle of five concentric rings:

- At the center are religious sites.

- Surrounding them are the working areas, such as the souks.

- Next are the residential quarters.

- These are encircled by the city walls.

- Finally, beyond the walls lie the gardens, orchards, and cemeteries.

Today, some 30,000 craftsmen still practice their trades in narrow alleyways and small workshops. For Sufis, Islam’s most mystical followers, Fez has long been considered sacred ground. The medina is dotted with zaouias—Sufi sanctuaries where brotherhoods gather to worship and sing. Their musical chants echo through the labyrinthine streets, forming the soundtrack of Fez—the auditory embodiment of the city’s profound spiritual essence.

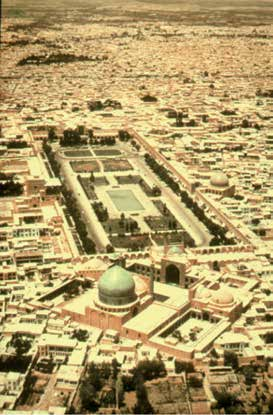

Shiraz

Shiraz is situated in a fertile valley nestled between two mountain ranges. These ranges act as macro-scale walls, defining a distinct regional space within which the city’s positive form has evolved. This sense of regional “place” (Makan) is further emphasized by the thoughtful placement of landmarks within the surrounding landscape.

Ancient Sassanian bas-reliefs, carved into the cliffs of a mountain pass leading to the city, serve as symbolic gateways, reinforcing the sense of entry into a vast and meaningful geographic zone. In later Islamic times, a brick arch known as the Quran Gateway was constructed at this pass. A Qur’an was once placed in a chamber above the arch, giving the gateway its name¹⁴.

The earliest known reference to the city—Tiraziš—appears on Elamite clay tablets dated to 2000 BC. By the 13th century, Shiraz had become a prominent center of art and literature, thanks to the support of its rulers and the presence of many Persian scholars and artists. Today, Shiraz is celebrated as the city of intellectuals, wine, flowers, and—most famously—poets, such as the 14th-century lyric poet Hafiz, whose verses are memorized by generations of Iranians and widely quoted as proverbs and everyday sayings.

Shiraz is also known as the city of gardens, roses, and nightingales, owing to its lush gardens and orchards. The renowned Eram Paradise Garden marks the beginning of a garden tradition that continues into the city center, where the shrine and madrasa of Shah-e-Cheragh attract both pilgrims and admirers of architectural beauty.

Throughout its long history, Shiraz has also been home to significant Jewish and Christian communities, and it continues to be one of Iran’s most open, receptive, and numinously beautiful urban centers (see Fig. 5).

Key Principles of Transcendent Cities

From these brief glimpses into some of the most sublime cities of the Middle East, several key characteristics emerge—insights that may inform principles for achieving greater urban transcendence in our future cities. They also offer possible strategies for revitalizing existing urban fabrics, many of which have succumbed to phenomenal and spiritual decay.

A critical question arises: Can the current surge of religious movements in the Middle East foster a renewed spiritualism, or is that potential being overshadowed—perhaps even suppressed—by the forces of radical fundamentalism¹⁵?

The Structure of Being

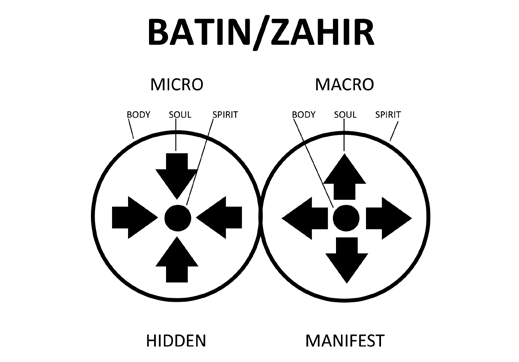

In traditional worldviews, human understanding leans toward a mode of comprehension that embraces both metaphysical and phenomenal interpretations of life. This dual understanding deeply influences perception, beginning with the individual’s situational awareness within the cosmos.

In this framework, cosmic space is perceived as an externalization of macrocosmic creation, which is in turn understood as analogous to the microcosm of the human self. This worldview—rooted in Hermetic philosophy and absorbed into Islamic metaphysics—divides the structure of the universe into two interrelated realms:

- Zahir (the outward, phenomenal macrocosm)

- Batin (the inward, hidden microcosm)

Each of these realms is further subdivided into three primary levels of being:

- Jism – the body

- Nafs – the soul

- Ruh – the spirit

This tripartite model reflects a sacred cosmology that traditionally shaped urban form, spatial awareness, and spiritual symbolism in transcendent cities¹⁶ (see Fig. 6).

Orientation in Space

In a structured cosmological space, traditional man possesses a clear sense of direction and belonging. His understanding of orientation is not arbitrary but rooted in the natural order—anchored by the heavens, the rising and setting of the sun and moon, the rotation of stars, and the movement of prevailing winds. These celestial and environmental phenomena make the otherwise infinite nature of space both measurable and meaningful.

The six cardinal directions—north, south, east, west, up (zenith), and down (nadir)—form a primary coordinate system by which all of creation is situated. Within the Islamic worldview, this cosmic structure is further enriched by the daily orientation toward Mecca for ritual prayer, transforming spatial awareness into an act of spiritual alignment¹⁷.

The Sense of Place and Sustainable Urbanism

Once cosmic order is perceived, the interpretive mind seeks a reflection of that order in the regional landscape. Place-making begins with responding to the natural environment—from distant mountain peaks to river valleys, ocean vistas, or desert plateaus. These settings become part of a site’s Genius Loci—its spirit of place—which guides the urban form, density, texture, and key visual axes.

Though Middle Eastern bioregions have definable geographic limits, their identity is also shaped by mythic and historic self-conceptions. This bioclimatic cultural identity can inspire a new spiritual ecology—not only for emerging urban centers but also for the retrofitting and healing of existing cities.

The most profound challenge lies in shifting from an anthropocentric to a biocentric norm of progress, where cities harmonize with their environments and metaphysical meanings.

Ancient Origins and Cosmic Consciousness

Cities founded in ancient times often appear more deeply imbued with cosmic consciousness. Perhaps this is because the founding motivations of early builders were shaped not only by strategic or defensive needs, but also by a mystical participation in life. They designed cities that resonated with universal order.

But what of the new cities—those that will emerge as humanity urbanizes at unprecedented scale? With global population expected to surpass 9 billion within the next 50 years, and more than 60% living in urban centers, the imperative is clear: new cities must offer more than just functionality—they must offer meaning.

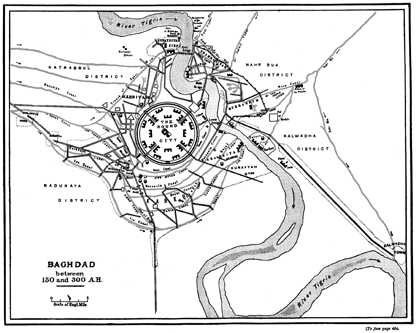

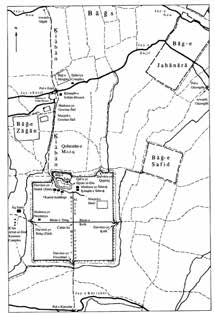

Modern astronomy and cosmology—from the Big Bang to the expanding universe—could offer fresh narratives to guide contemporary urban form. Historically, great cities have served as abstract projections of human worldviews inscribed onto the Earth. From the ritual landscapes of Göbekli Tepe, to Elamite Choga Zanbil, Ecbatana, the circular city of Baghdad under Caliph al-Mansur, and Herat in 12th-century Afghanistan, cities often expressed the conceptual structure of the universe as understood in their time (see Figs. 7, 8, 9).

Their purpose was to manifest tawhid—the metaphysical principle of divine unity. Yet within this unity, the contemplative mind recognized multiplicity: the harmony of many within the One, and the presence of the One within the many. This philosophy shaped the dynamic and rhythmic urban geometries of cities like Shiraz and Isfahan during the 16th century¹⁸ (see Fig. 10).

A New Urban Vision

Can a renewed macrocosmic consciousness—one that respects the metaphysical and ecological dimensions of life—help shape the city forms of the future? Can this vision also scale down to accommodate the microcosm of the individual, the intimacy of the family, and the shared life of neighborhoods?

The cities of the past suggest it is possible. The challenge before us is to bring that transcendent vision into contemporary urbanism, creating places that are both cosmically inspired and human-centered.

Sacred Paths, Places of Religion & Pilgrimage — Places of Knowledge

Without exception, the selected cities mentioned above each shelter one or more sacred sites—shrines, sanctuaries, or religious places of pilgrimage. The sanctity of their spirituality permeates not just these sites, but extends throughout the urban fabric, infusing key places with meaning and resonance. Sacred pathways and historic pilgrimage routes often weave organically through the city, forming a spiritual skeleton that continues to shape their physical and metaphysical presence¹⁹.

Over time, many of these cities have also become centers of knowledge, housing institutions of academic and spiritual learning. This has given rise to vibrant student life, endowing these places with a sense of artistic, intellectual, and social vitality. The presence of wisdom traditions coexists with contemporary education, producing cities that are as reflective as they are dynamic.

Urban Space, the Public Realm, and the Paradise Garden — Pedestrian and Human Scale

One of the defining features of the cities cited is the positive and vital concept of space. These urban environments are not shaped merely by form or monumentality, but by the quality of spatial experience itself. The idea that space should lead form is central to their design logic.

Dense urban fabrics—such as those seen in Isfahan, Iran—are punctuated with public spaces that celebrate the pedestrian scale. These include linear bazaars, open plazas, and public gardens, all designed with human proportions in mind (see Fig. 11). They are walking cities—organic, lived-in environments animated by conversation, music, and movement.

Urban structures typically range from two to four stories, composed of courtyard-centered volumes, shaded passageways, and serendipitous vistas, often anchored by symbolic buildings of architectural quality. These spaces foster a deeply human and sensory experience of the city.

Multicultural, Integrated Communities — Political History and Economic Vitality

Another common trait of transcendent cities is their openness to multiculturalism. These are cosmopolitan environments where people of different faiths and ethnicities coexist, shaping rich and diverse cultural tapestries. This pluralism may hint at a deeper, shared foundation of spirituality that transcends individual doctrines—a quality essential to the sublime city.

These cities are not cloistered or monastic; on the contrary, they often pulse with artistic, sensual, and civic energy. Many have served as seats of political power or regions of strategic influence, and most maintain thriving economies characterized by markets such as the Souk or Bazaar. A notable example is the Khan el-Khalili market in Cairo, a historic commercial hub still vibrant today (see Fig. 12)²¹.

Quality Architecture

One profound definition of architecture is that it is “the process of creating Archetypes.” In contrast, other definitions often result in the production of mere buildings, which, when visualized as part of a pyramid of values, occupy the lower rungs of quantity, far removed from the apex of qualitative and aesthetic excellence.

Cities that have nurtured what is both beautiful and good—in Aristotelian terms—radiate a subtle elegance. This elegance is not the product of material extravagance, but rather the essence of their conception and realization. In such cities, proportion, the use of numbers, and geometry serve as mathematical expressions of deeper, timeless truths. These elements aim to recall the Archetypes—whether through the Platonic “world of hanging forms” or the Islamic concept of Alam-i-Mithal, the imaginal realm of perfected forms²².

The Hermetic traditions of alchemy offer further insight for the architect. They provide metaphysical and symbolic guidance for the transformation of matter—from basic heaviness to elegant lightness—through the disciplined and conscious use of symbols, colors, geometry, and mathematics. These principles are often embodied in sacred landscapes, such as the Paradise Gardens of the Islamic world.

A compelling example is the 19th-century Bagh-i Eram in Shiraz, Iran, where geometry, symbolism, and aesthetic intention converge to create a spatial experience that transcends the material (see Fig. 13).

Transcendent Symbolism

Traditional man possesses an innate propensity for symbolic expression, a tendency deeply embedded in both Persian and Arabic languages and cultures. In Persian, one may say a person has Ham-dami—an inner resonance or sympathetic connection with the batin (hidden or inward) qualities of creation.

Within traditional metaphysics, symbols are regarded as theophanies—manifestations of the absolute within the relative, phenomenal world. These symbolic forms, though sensible and perceptible, point toward a deeper metaphysical reality. They are not human inventions; rather, *“man does not create symbols, he is transformed by them.”*²³

Philosopher Thomas Berry notes that traditional man lives in intimate communion with the depths of his psychic structure, a state that contrasts sharply with the rationalistic orientation of modern Euroamerican consciousness. As Berry writes, *“We have so developed our rational processes, our phenomenal ego, that we have lost much of the earlier communion we had with the archetypal world of our own unconscious.”*²⁴

Supporting this, Pulitzer Prize–winning biologist Edward O. Wilson, in Consilience, explains that the human brain tends to condense repeated experiences into symbolic concepts. These mental abstractions, which he terms memes, are neural activity patterns that represent the core units of culture. His research shows that people are naturally drawn to environments that resonate with their inherited symbolic inclinations. As Wilson asserts:

*“The message from geneticists to intellectuals and policymakers is this: Choose the society you want to promote, and then prepare to live with its heritabilities.”*²⁵

Similarly, in The Faith Instinct, Nicholas Wade traces the origins of spiritual longing as a genetically hardwired instinct—a survival mechanism rooted in the evolutionary past. Even in today’s increasingly secular societies, faith and the spiritual impulse remain vital forces that continue to fortify the social fabric²⁶.

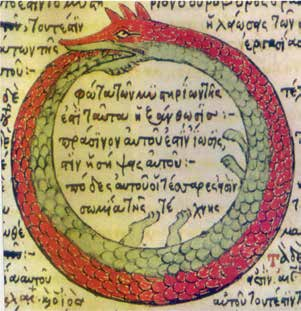

Psychologist Carl Jung also emphasized the timeless power of symbolic forms—including mandalas, circles, Pythagorean geometries, colors, the Ouroboros, and mythic archetypes such as heroic figures, natural elements, and the Earth Mother. These symbols, he argued, are ever-present in the collective unconscious, waiting to be awakened by those who have *“the conscious eyes to see.”*²⁷ (See Fig. 14)

Concluding Observations

Such, then, is the nature and framework of this quest: to shift our cities and their architecture away from a machine-inspired, functionalist aesthetic toward a more cosmic, ecological, and spiritually inspired design approach. The resolutions to these values and aesthetic questions remain elusive, yet they offer profound inspiration for more meaningful answers that touch both the individual soul and collective humanity.

“When you become the pencil in the hand of the infinite,

When you are truly creative… design begins and never has an end.”

— Frank Lloyd Wright²⁸

To truly address the key issues of sustainability and realize the highest aspirations of contemporary art and architecture, a common ground must be found. Without it, new architectural creations lack a sense of place, become environmentally unsustainable, and appear as alien intrusions upon existing civilizations. This identity crisis is palpable throughout the cities of the Middle East, particularly within the rapid urban expansions of the Persian Gulf region.

Instead, the momentum of this new, resurgent urbanism urgently demands design solutions that harmonize with both nature and culture.

“Every advance in technology has been directed toward man’s mastery of his environment. Until very recently, however, man always maintained a certain balance between his bodily and spiritual being and the external world. Disruption of this balance may have a detrimental effect on man, genetically, physiologically, or psychologically. And however fast technology advances, however radically the economy changes, all change must be related to the rate of change of man himself. The abstractions of the technologist and the economist must be continually pulled down to Earth by the gravitational force of human nature.”

— Hassan Fathy²⁹

To restore cultural identity, we must begin with a cosmic, systemic awareness of the context of human existence—both on the tangible, phenomenal level and the less tangible, cultural level. We need to understand the particular worldviews of indigenous civilizations, the Genius Loci (spirit of place), and the optimal ecological fit between cities and their natural context.

The mandate of good design is to elegantly realize this holistic vision in physical form. Such an approach offers a vital methodology for reconciling the profound worldviews of traditional civilizations with the demands of contemporary urban life.

References

- Steele, J. Architecture for the Poor: The Complete Works of Hassan Fathy (1997)

- Bronowski, J. The Ascent of Man

- Ellul, J. The Technological Society

- McHarg, I. Design with Nature

- Berry, T. The Dream of the Earth

- Ibid.

- Ali, A.Y. The Holy Quran

- Bukhari, I. Sahih al-Bukhari

- Harvard University Symposium YouTube DVD titled: Urbanism, Spirituality & Well-Being (June 2013)

- Mann, C.C. “The Birth of Religion: The World’s First Temple,” National Geographic, Vol. 219, No. 6 (June 2011)

- Polz, Daniel C. “Thebes.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt

- Ardalan, N. Blessed Jerusalem

- Burckhardt, T. Fez, City of Islam

- Ardalan, N. / Bakhtiar, L. The Sense of Unity

- Nasr, S.H. Islam in the Modern World: Challenged by the West, Threatened by Fundamentalism, Keeping Faith with Tradition (2010)

- Ardalan, N. / Bakhtiar, L. The Sense of Unity

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Barrie, T. Spiritual Path, Sacred Place: Myth Ritual and Meaning in Architecture

- Ardalan, N. / Bakhtiar, L. The Sense of Unity

- Raymond, A. The Great Arab Cities in the 16th-18th Centuries: An Introduction

- Ardalan, N. / Bakhtiar, L. The Sense of Unity

- Nasr, S.H. Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines

- Berry, T. The Dream of the Earth

- Wilson, E.O. Consilience

- Wade, N. The Faith Instinct

- Jung, C.G. Man and His Symbols

- Geva, A. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Sacred Architecture

- Steele, J. Architecture for the Poor: The Complete Works of Hassan Fathy (1997)

Published in 2A Magazine# 26, Winter 2014