Credits: Mohammad Gharipour

Introduction

In the contemporary Middle East, bureaucratic and corporate interests seem to have become the primary drives of architects. Global capitalism, rather than being an accommodating element, is often portrayed as an inevitable consequence driven by the economic self-interest of a newly conscious consumer class.¹ In capitalist societies, the value of architecture tends to be defined not by its spiritual, intellectual, or emotional content but by its economic worth.² This economic environment has influenced the psychology of architects, whose bureaucratic or organizational personalities compel them to submit to an economic power system for money and prestige.

The globalization of markets has been a powerful economic, political, and cultural force. However, in prioritizing economic growth at any cost, this form of global capitalism has begun to deteriorate from within.

Following World War II, the availability of building materials and technologies that standardized fabrication and construction spread to countries in the Middle East. Native and foreign architects explored a variety of approaches and new forms to express emerging functional needs. Alongside economic progress and shifting socio-cultural and geopolitical contexts, contemporary architecture in this region faced the challenge of developing a distinctive character that combined the heritage of regional building traditions with the demands of modern society.

This evolution included the creation of new building types, the use of innovative materials and technologies, and the revival of Islamic building traditions adapted to growing industries and urban infrastructure.

In this age of pluralism and global capitalism, Middle Eastern architecture has become tremendously diverse, defying any simple generalization. While architects in the region do not appear motivated by universal stylistic labels, and questions of style as predetermined icons seem outdated, the retention of regional identity remains a vital concern.

By applying a universal framework, this paper examines regionalism in contemporary Middle Eastern architecture.

What is Regionalism?

In contemporary society, culture is complex and diverse to such an extent that no critic or architect can consistently address all of it. Amidst such pluralism and nostalgia, architects must seek new styles.³

As a response to the neglect of local cultures in modern architecture, critic Kenneth Frampton introduced regionalism as a strategy of resistance in 1977. He argued that the survival of rooted cultures depends on their capacity to reconstruct their traditions while appropriating foreign influences, both culturally and civilizationally.⁴ Regional identities can temporarily resist the maximization of profit and efficiency.⁵

Frampton’s concept of critical regionalism—distinct from vernacular architecture—was an avant-garde approach grounded in local or regional architectural principles. It emerged during the early 1980s as a reaction to the rising postmodern movement. In Towards a Critical Regionalism, Frampton explained how architecture can be modern while reconnecting with foundational sources and participating in universal civilization.⁶

This approach advocates adopting modern concepts for their universal and progressive qualities, while respecting the geographical context. To differentiate from postmodern historicism, Frampton proposed emphasizing topography, climate, light, tectonic form, and sensual qualities rather than scenographical or visual ornamentation.

Regionalism in the Middle East

Long before Frampton’s theory, local architects had already explored regionalism through the use of historic elements, forms, and materials. However, regionalism received limited attention mainly because of the public’s fascination with European and American architectural models.

Economic development and the rise of international construction firms after the 1970s accelerated the importation of modern architectural forms from the West. The use of steel, concrete, and glass became symbols of progress and prestige in cities, often devoid of critical discourse on modernism’s implications in the region. Ironically, early efforts to localize modern architecture were rooted in modern movements that were largely uniform from Turkey to Egypt.

Turkey, physically and culturally closest to the West, especially due to Atatürk’s modernization efforts in the early 20th century, experienced a pivotal period in the 1960s when Western International style coexisted alongside revived nationalistic architecture.

For example, the Turkish Historical Society Building (1966) by Turgut Cansever, inspired by Ottoman madrasa courtyard plans, features a large three-story atrium surrounded by interior spaces arranged around intricate trelliswork that poetically distributes natural light. Exterior walls are constructed from massive local stone resting on pilotis.

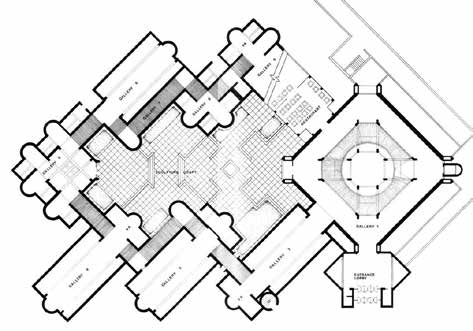

Modernization in Turkey and Iran was almost synchronous, as their rulers, Atatürk and Reza Shah—close allies and friends—shared ideas about foundational reform. In the 1960s, Iranian architects began to revive Iranian identity for modern life. Notable examples include the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran (1976), where regional symbols and spatial organization are integrated into the plan, and the Shushtar New Town Housing Complex by Kamran Diba (1974–1978), which creates spatial dynamics between living units and a series of narrow outdoor courtyards, elements inherited from traditional Iranian cities and towns (Figures 1 and 2).

In Egypt, Hassan Fathy was a pioneering architect whose focus on community issues through the use of traditional and classical forms was sometimes criticized by his peers as too conservative. Nonetheless, Fathy’s style and emphasis on local values influenced a new generation of architects who were also engaging with Western architectural movements.

With the rapid growth of urban centers during the 1970s, one significant project in Cairo was Abdelbaki Ibrahim’s Center for Planning and Architectural Studies (1979). Ibrahim combined modern construction technologies with traditional building concepts—such as scale, layering of volumes, spatial organization around a central courtyard, and the use of local materials—to revive historic Islamic architectural traditions within a modern urban framework. Although the building does not feature signature historic elements like arches, domes, or vaults, it embodies traditional values through its proportions, construction methods, and sensitive response to local environmental and cultural conditions.

The last decade of the 20th century saw major economic growth in urban centers, which in turn created a demand for new architectural expressions by both local and international architects. During this period, public projects in Syria, such as the Azbakiya Commercial Complex (1980) and the Syrian General Insurance Company Building (1984), combined modern formal sensibilities, materials, and structural systems with traditional principles—incorporating central courtyards and gardens as integral components of their spatial configurations.

Neighboring Lebanon followed a similar trajectory in its embrace of modernism. Over several decades, projects such as Broummana High School (1966), Pine Forest Mosque (1968), and Harissa Cathedral (1970) reflected a thoughtful engagement with modernist principles within the local context. These buildings incorporated regional traditional elements, including central courtyard plans, solid-to-void relationships, and arches.

The foundation of various legislative agencies and the growing demand for urban infrastructure development have led to multiple iterations of city planning for Beirut over the past three decades (Figure 3).

In Saudi Arabia, two contrasting architectural approaches—modernist and classicist—developed simultaneously, resulting in an absence of a hybrid style. As part of the commission to revitalize New Jeddah, the Corniche Mosque (1986–1988) and the Ruwais Mosque (1989), designed by local architect Abdelwahed Al-Wakil, embodied a contemporary architectural style grounded firmly in a traditional vocabulary.

Another significant project was the Hajj Terminal (1982), designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) in collaboration with Fazlur Rahman Khan. This building typology emerged in response to a growing economy and the increasing demand for air travel. Characterized by its distinctive tensile roof and structural components that evoke ancient nomadic tent structures, the Hajj Terminal utilized the latest technological innovations while abstracting elements of local architectural heritage.

These projects in Saudi Arabia have not only become landmarks within the modern urban landscape but also serve as architectural reinterpretations of traditional building components adapted to contemporary building typologies (Figure 4).

Similarly, architecture in the Persian Gulf region experienced rapid development following the growth of the oil economy in the 1970s. In Kuwait, traditional architectural vocabulary—including spatial layouts, formal elements, proportions, arches, domes, color schemes, and ornamental details inspired by earlier regional precedents—was combined with geometric rhythm and contemporary materials, primarily reinforced concrete. Notable examples include the Sief Palace (1983) and the Kuwait State Mosque (1983).

As in other Gulf countries, projects built after the 1970s in Qatar faced the challenge of abstracting historical architectural traditions—such as rhythm, volumetric relationships, and natural lighting conditions—within a contemporary design language and modern material palette. Religious buildings like the Um Said Mosque (1981) and the Oman ibn Affan Mosque (1984) similarly blended regional design principles with modern approaches.

The campus plan of the University of Qatar (1983–1985) embodied dominant Modernist principles, including grid planning, rigid geometric order, and concrete construction. Yet it also integrated local historic forms inspired by ancient wind towers, courtyard plans, and a carefully controlled use of natural light to respond to both cultural and climatic contexts.

Traditional housing architecture in the UAE, marked by tall wind towers, courtyard plans, and dense development along narrow streets, evolved as a climatic response to the local humid environment. However, with the rise of the oil industry and the importation of new materials such as cement, traditional forms and building methods were gradually replaced by cement block construction and modern forms.

The financial boom of the 1990s triggered a dramatic transformation of the skyline and urban landscape, resulting in the construction of numerous towers and urban complexes. These new buildings combined postmodernist trends with references to local traditions, achieving engineering milestones through the use of steel and reinforced concrete. Iconic examples include the Al Attar Tower (1997) and the Burj Al Arab Hotel Tower (1994–1999) (Figures 5 and 6).

The Aga Khan Award for Architecture, established in 1977, has been a strong advocate for regional projects in developing countries. This prestigious award has recognized numerous initiatives across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia that embody Islamic identity within the built environment while responding thoughtfully to their local socio-economic contexts. Spanning a diverse range of building types—from religious structures and social housing to contemporary high-rise developments—the award celebrates projects that innovate modernity while preserving cultural identity.

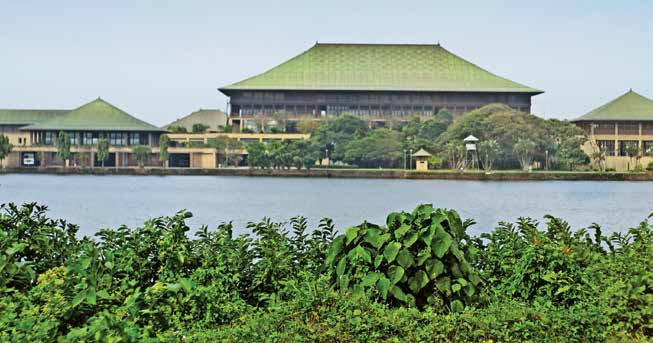

Rather than simply replicating historic precedents, the award highlights designs that reinterpret and enrich tradition within a contemporary framework, thereby imparting new meaning to the people and cultures they serve. Geoffrey Bawa, a recipient of the Aga Khan Chairman’s Award, stands out as one of the most successful regionalist architects in the Islamic world. Bawa developed a distinctive style of tropical regionalism, drawing upon traditional elements such as cantilevered floors, stepped roof pavilions, fountains, and asymmetrically arranged low-rise pavilions organized around courtyards (Figure 7).

Conclusion

A wave of rapid economic growth fueled by rising oil prices has created significant opportunities for international architects and construction firms in the Middle East. However, ongoing economic and political instabilities have introduced a sense of discontinuity, impermanence, and irregularity to the region’s development. Despite these challenges, the market remains the most influential factor shaping architecture in the area.

The recent decades’ economic expansion, commercialism, consumerism, and intensifying global capitalism have made the Middle East an ideal testing ground for architectural creativity. Concurrently, the digitization of design processes, the influx of international architects, and increasing investment in construction projects have obscured a clear architectural progression. The homogenization of architecture since the 1960s contrasts sharply with the rich diversity of the region’s cultures and societies. This tension between the global capitalist drive toward uniformity and the national desire for difference has complicated architectural practice.

Moreover, recent sociopolitical and cultural movements have propelled the region into an age of complexity and contradiction. Contemporary architecture in the Middle East is no longer a monotonous or universal phenomenon. Yet, the current chaos of stylistic pluralism reflects less cultural diversity than architects’ egocentric approaches and the region’s social and economic complications.

What then is the future of regionalism in the Middle East, and how can it be supported by decision-makers? A genuine commitment to regionalism requires a deep appreciation of local and regional values, traditions, and architectural elements alongside advanced technology, materials, and techniques. Critical regionalists, as Kenneth Frampton described, were originally modernists fluent in modern architectural language. Any contemporary solution inspired by regionalism must embrace the complexity, diversity, and pluralism inherent in the region’s cultures.

Contrary to modernist ideals, architects now recognize that there is no utopia or magic formula for architectural perfection. Success depends on a thorough understanding of contextual issues, which demands dynamic dialogue among architects, planners, communities, and users—an engagement largely neglected over the past sixty years in the Islamic world. Therefore, the challenge is not the absence of regulations or codes, but rather their implementation and the lack of public participation.

At the same time, efforts to innovate and create ‘new’ architecture must be coupled with initiatives to preserve the ‘old.’ The rapid development of new urban areas has resulted in the demolition of numerous historic buildings, underscoring the need for development plans to include strategies for preserving and rehabilitating old buildings and historic urban neighborhoods.

References

- Reinhold Martin, Utopia’s Ghost (University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2010), p. 27.

- Suzi Gablik, Has Modernism Failed? (Thames and Hudson, London, 2004), p. 49.

- Collin Rowe, “Introduction to Five Architects (1972),” in Architectural Theory: An Anthology from 1871-2005, Volume II, edited by Harry Francis Mallgrave and Christine Contandriopoulos (Blackwell Publishing, 2008), pp. 400–402, p. 400.

- Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture and Its Critical Present (London: Architectural Design, 1982), p. 77.

- David Kolb, p. 165.

- Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, edited by Hal Foster (Bay Press, Port Townsend, 1983).

- Mohammad Gharipour and Anitha Deshamudra, “Contemporary Architecture in the Middle East (1900 – 2000),” in Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, edited by Orlando Patterson (New York: Sage Publishers, to be published in 2011).

Published in 2A Magazine# 26, Winter 2014